The South Asian Communities

A history of the South Asian communities in Rossendale

During the immediate post-war period, migrations began as a result of a combination of economic and political developments. After the war ended in 1945 Britain faced huge challenges. The economy had to be rebuilt and it was a time of great social change. The NHS was established, slums were cleared and industries began to expand. Servicemen and women returned from the war expecting better conditions at the workplace and were no longer prepared to accept pre-war standards of unsocial work with long hours and low pay.

It was also recognised by the UK government that there was a shortage of labour, so Britain looked for workers from Europe and the countries of the Commonwealth, particularly the West Indies, India and Pakistan. The Royal Commission on Population reported in 1949 that immigrants of ‘good stock’ would be welcomed ‘without reserve’.

Karachi, Pakistan c. 1950

Working in Lancashire

The textile industry, on which Lancashire’s prosperity had depended, had been in decline before the war but in 1945 there was confidence that it could recapture some of its past glories if it was able to massively reduce its costs. As a result the industry enthusiastically grasped the opportunity offered by men emigrating from overseas to work in the cotton mills. The majority of these jobs were low paid and in the least popular shifts, such as night work. Efforts were made in the colonies to spread the word that Britain was looking for young, able-bodied, men to leave and seek work in British industry. Visas and passports were made easy to obtain through the 1950s and ’60s.

For most of the men, when they first arrived in Rossendale, living conditions were fairly primitive. Few of the houses they rented would have had baths; toilets were usually in outhouses and often not connected to the sewers. In the 1960s this wasn’t unusual; many people in Rossendale lived in similar conditions. Initially, it wasn’t unusual for 10 or more of the immigrant workmen to rent a house together, sharing a limited number of basic dormitory-type beds to cover different shifts at the mill.

Few of the men spoke English particularly well, and as a result were unable to understand what services were available to them. As a result the refuse collection system, council wash facilities (such as slipper baths, available at the municipal pools), medical and housing services, were all difficult to access. Because most of these men still expected that their sojourn in Lancashire would be a temporary one, very few – at first – gave any thought to creating support networks of their own.

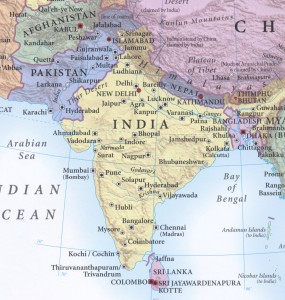

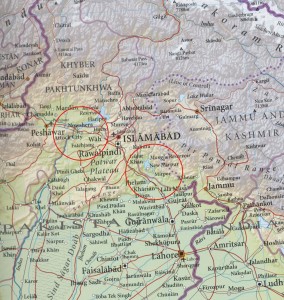

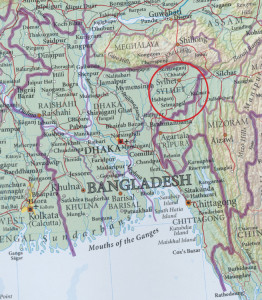

Map of India showing Pakistan and Bangladesh

Things begin to Change

Slowly things began to change. A few of the men got together to set-up informal support groups and organise themselves. Many of the testimonies from people interviewed for the Different Moons project dwell on this period. The struggle to improve their living conditions and life-style, and the slow process of saving in order to send money home, purchase houses and gain control of their own living requirements, dominated much of their limited spare time.

Many friendships were made with the host community, and there are frequent stories of support and help that the immigrants experienced. Equally there were the challenges of racism and intolerance to be confronted.

For both the immigrant and host communities things changed substantially during the first 25 years following the arrival of the first South Asians to Rossendale. From the 1970s onwards there had been much debate about UK immigration policy, and successive governments began programmes of legislation to restrict the rules governing the right to immigration. This both contributed to, and coincided with, a recognition among many South Asian workers that their move to Lancashire was likely to be for months or years, and in fact for many became a permanent one.

From this period onwards, women, and sometimes children and parents, began to move from Pakistan or Bangladesh to be with their menfolk. Families now settled in Rossendale together and, as a result, the nature of the South Asian community changed dramatically during this period.

Pakistan, showing Attock and Mirpur regions

At work, in housing, and in education South Asians often faced the challenges of misunderstandings and discrimination. To escape these problems and to improve their standard of living and escape factory work, many became self-employed. The Lancashire textile industry was by now clearly failing; Asian-owned businesses started to create their own jobs, while others worked to increase awareness and change practices within institutions. As this happened they inevitably began to contribute more and more to the local economy and community.

Where the SA communities came from

Most of this new workforce were from Pakistan, which was a major producer of cotton and jute and so had existing trade links with Lancashire. Pakistan had been initially divided into West and East Pakistan after Partition from India in 1947, but in 1971 East Pakistan seceded after a period of war and bloody struggle to became the independent county of Bangladesh. The majority of the men who came to work in Lancashire fully expected to return to their homes in Pakistan or Bangladesh after a period working here during which they would save sufficient money to guarantee a decent future for their families.

From Pakistan the main areas of migration were the villages around the town of Attock in the north-west, and many people in Haslingden come from this area (note that there iare both a Haslingden-based Attock Travel and an Attock Taxi Company) and from Mirpur, closer to the border with Kuwait. In Bangladesh the main centre of emigration was Sylhet, then a poor region in the east of the country, and many people from Mirpur region and Sylhet settled in Rawtenstall.

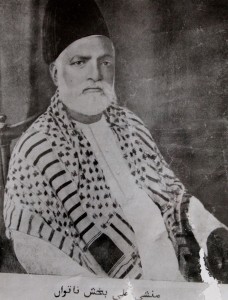

Family photograph: Courtesy Mrs S Hussain

Each of these regions spoke different languages – Urdu is the official language of Pakistan, although Punjabi is also spoken along with dialects such as Hindku. Many of the immigrants from the north and west of the country were Pashtuns, speaking Pashto, while Bengali (or Bangla) was the language of most Bangladeshis, though many who came to Rossendale speak a Sylheti dialect.

Communications between Lancashire and the homeland were difficult. There were very few telephones, both in the UK and in the villages in Pakistan and Bangladesh. Telephone lines were notoriously unreliable. As a result the new arrivals found it very difficult to keep in touch with families and friends back home, postal and telegram services providing the main means of contact. Feelings of loneliness and isolation were very common and hard to bear.

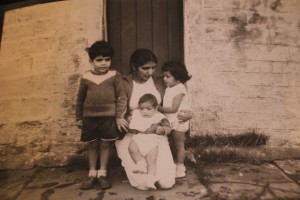

Family photograph: Courtesy Mrs W Azfar

Current connections

In the sixty years since the first South Asian immigrants arrived in Rossendale things have changed beyond recognition. Families originally from Attock or Sylhet now have three generations settled and at home in Rossendale. Despite this, strong links with the mother countries have been retained, and individuals and families often return regularly to the villages in Pakistan or Bangladesh that their grandparents left 50 or more years ago.

In the sixty years since the first South Asian immigrants arrived in Rossendale things have changed beyond recognition. Families originally from Attock or Sylhet now have three generations settled and at home in Rossendale. Despite this, strong links with the mother countries have been retained, and individuals and families often return regularly to the villages in Pakistan or Bangladesh that their grandparents left 50 or more years ago.

A settled community of South Asian families has developed in Rossendale. It has opened mosques for worship, and shops and businesses to cater for food and other necessities. Throughout Britain cultural exchange has resulted in exciting fusions of music, art and cuisine. Second and third generations of young people from Asian families took the opportunity to study in college and universities. Many of these families have achieved a prosperity that the first generation of immigrants would have been astonished to witness, even when it may have been their original aspiration and dream.

However, as a result of rapidly changing economic circumstances and overseas policies there is evidence of a recent growth in Islamaphobia within the UK. This has created a new set of challenges and, as in earlier years, women continue to play a significant role in challenging expectations from within and perceptions from without. No doubt the whole community will continue to rise to these complex challenges to create an ever more intricate social tapestry.

The Different Moons project has, we hope, made a small contribution to this process and has played a part in celebrating a local South Asian heritage community that is vibrant and visible and here to stay, very much part of Rossendale as it is in the twenty-first century.

Map of Bangladesh, showing Sylhet